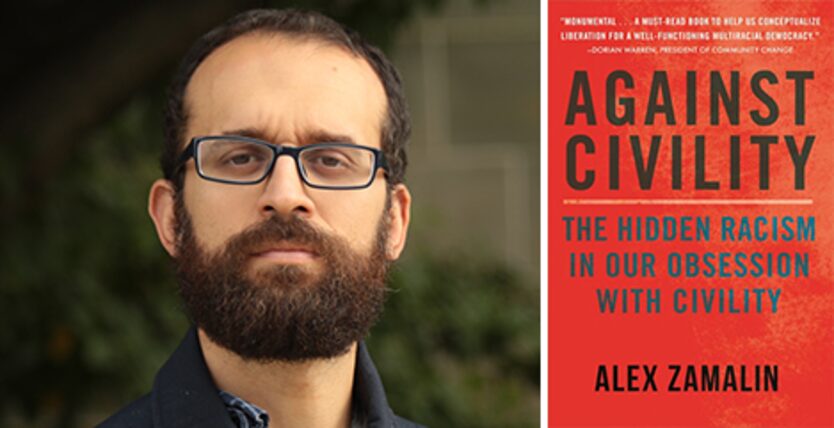

Instead of Calls for ‘Civility,’ We Need Civic Radicalism: Alum Alex Zamalin on His Latest Book

Alex Zamalin (Ph.D. ’14, Political Science) has published a book almost every year since defending his dissertation. The latest, Against Civility: The Hidden Racism in Our Obsession with Civility, shows how calls for civility from both the right and the left have been used to hold back Black social activists and justify violence against Black Americans since the nineteenth century.

Zamalin, who is a professor of political science and director of African American Studies Program at University of Detroit Mercy, recently discussed his new book with the Graduate Center:

The Graduate Center: Calls for more civility have come from across the political spectrum. Do you see any contexts in which civility would be helpful?

Zamalin: Part of what I try to demonstrate in the book is that civility has such a fraught and racialized history that, despite our best efforts to use civility for racial justice, the effort is always going to be inadequate, fail outright, or monopolized by the very forces that want to promote inequality or are comfortable with a certain level of inequality.

Which is to say I think that, yes, of course, there’s a difference between those on the right who say we need more civility and we need to ensure that more right-wing voices are brought into the conversation, and those on the center-left who say we need to all get together and try to reach a kind of consensus in a civil way. However, I think whenever you introduce the language of us versus them, civil versus uncivil in the political arena — which is an arena of power and inequality — you often tend to empower the very forces that want to discipline, punish, chastise, and castigate the very populations that historically have never been allowed to determine the rules of who is civil and who is not.

GC: How has the concept of civility been used to maintain inequality in American history?

Zamalin: One of the things that I tried to do throughout the book is distinguish between the various uses of civility, and there’s one use which is more often than not taken up by right-wing reactionary forces to demonize opposition and folks who are engaged in political activity. I’m thinking about the 1898 Wilmington race massacre, when a mob of 4,000 came into the city of Wilmington, which had a Black-led government, and essentially destroyed the town. I’m also thinking of all the various instances of racialized violence against Black citizens today who are not doing anything apart from literally living their lives, but they’re deemed uncivil because of their race.

The other use of civility, the more pernicious and the more insidious, is trying to use it as a way to silence righteous protest and dissent. For instance, at the height of the civil rights movement in the 1960s, many liberals and moderates were urging Martin Luther King to go slow, to have patience, to not break curfew in Birmingham, to not protest against white supremacy in Georgia and Mississippi. And King essentially said that patience is the tool of power and this is an unacceptable way of calling out activists for being interested in racial justice and trying to struggle disruptively for racial justice

GC: In your book, you said that instead of civility, you’d like to see civic radicalism. How do you define that, and how is it different than civil disobedience?

Follow Us